Guyana´s Road to First Oil: The Quest for Technical Cooperation and Economic Diplomacy

Embajador Iván Roberto Sierra Medel *

Resumen:

El presente ensayo describe la situación actual de la economía de Guyana, ofreciendo una perspectiva de las situaciones que podrían presentarse a medida que la explotación comercial de los campos petrolíferos en alta mar despliegue su enorme potencial. Dentro del texto, el autor señala que la industria de petróleo y gas en Guyana, es posible con un enfoque equilibrado, teniendo en cuenta tanto la producción de energía como la protección ambiental. El texto destaca también la necesidad de que el país aproveche la nueva fuente de riqueza con las fortalezas tradicionales de la agricultura. Por último, se ofrece un panorama de las experiencias recientes en la relación bilateral con México, en materia de cooperación técnica y diplomacia económica, así como lecciones aprendidas, sumandos así a los esfuerzos de ambos países en favor de una amplia transformación económica en las siguientes décadas.

–

As countries around the world, and especially those with the most challenging gaps to bridge, engage in multi-actor strategies aimed at achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) within the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the need for adequate levels of financing is a pressing concern. Although there is near-consensus on the nature of the 17 global SDGs as cross-border partnerships that should elicit efforts from developing countries and industrial economies, the mainstay of resources that will fund investments in social development and productive transformation ultimately depends on sustained economic growth.

Thus, some may argue that development cooperation practitioners witness a Catch-22 situation: the one realistic shot of developing countries that lag behind significantly in terms of income and lack of domestic capacities to sustain GDP growth in order to build stronger economic foundations and social progress requires them to achieve economic growth basically as a prerequisite (although SDG 8 sees growth as a goal on its own merits). The growth paradox calls for a closer analysis from the point of view of economics and political science in order to devise creative and practicable solutions.

However, if the case can be made that anaemic GDP growth is effectively a burden that imperils sustainable development, that argument should not suggest that accelerated economic expansion provides all solutions by itself. Indeed, as the Cooperative Republic of Guyana, the country with the second-lowest per capita income in the Western Hemisphere, braces itself for an unprecedented 29% rise in GDP during 2019, the country seeks to cement existing development partnerships and to bring together stakeholders from all productive sectors in the endeavour to obtain the maximum benefits from its emerging oil and gas industry. The present essay will discuss the current situation of the Guyanese economy and the trends that could be expected as commercial exploitation of offshore oilfields unfolds its vast potential. The author will make the argument for a balanced approach in building Guyana´s oil and gas industry taking into account both energy production and environmental protection, and will highlight the need for the country to leverage the new source of wealth with traditional strengths in agriculture. Recent experiences in the bilateral relationship with Mexico concerning technical cooperation and economic diplomacy provide the empirical lessons learned regarding joint efforts to make a contribution to the present needs and to effect the broad economic transformation that Guyana will have the coveted opportunity for put in place in the next decade.

A land where vast opportunity coexists with limited economic progress.

Among English- and Dutch-speaking countries in the Greater Caribbean, Guyana ranks first in terms of landmass, third in terms of population, and has the sixth largest economy in terms of nominal GDP, but the country has been stuck for decades at the very bottom of that group of nations in terms of Per Capita Income. As of 2018, the only country in the Americas that lags behind Guyana in terms of Per Capita Income is poverty-ridden Haiti.

The undeniable disparity between the significant potential for development in Guyana on the basis of the country´s natural resources and the actual performance of the economy along many decades has widened the gap in terms of income and standards of living between Guyana and its better-off neighbours in the Caribbean.

The trifecta of a commodities boom, international tourism, and renewed dynamism of financial activities that lasted from 2002 until 2015 greatly propelled economic growth across the Greater Caribbean. The best performers, such as Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago, saw unprecedented growth of GDP (according to estimates by the World Bank, Per Capita Income in Barbados reached USD 16,129 in 2015, while the sustained spike of oil prices led to the trebling of Trinidad and Tobago´s Per Capita Income, as it went from USD 7,049 in 2002 to USD 20,081 in 2014)[1].

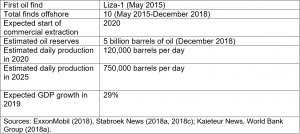

Table 1. An economic picture of the pre-oil era in Guyana.

Guyana only marginally benefited from the bout of regional prosperity, achieving a Per Capita Income of USD 4,030 in 2014. However, as the Guyanese economy relies on a relatively diversified portfolio of sources of hard currency (mining, agriculture, remittances, and fisheries), the country has sustained less damage than other Caribbean nations from the Perfect Storm (the confluence of tighter international restrictions to financial services, lower prices for commodities, tourism markets volatility, and large foreign currency-denominated debt) that has been pounding the region since 2014[2].

While the loss of economic momentum across the Greater Caribbean since 2015 has prompted a number of countries to enact economic reforms and to secure the help from the International Monetary Fund (Barbados, Jamaica, and Suriname are cases in point[3]), Guyana has been facing the need to better adapt to shifting economic prospects not because of a deterioration, but rather in view of new avenues of development made possible by the first oil discovery announced in May 2015 and the subsequent offshore finds that point to large recoverable reserves of oil and gas.

Guyana´s oil and gas game changer.

In May 2015, an international joint venture led by ExxonMobil announced that a test well in deep waters offshore Guyana had reached a vast reservoir of commercially recoverable oil.

The initial projections put estimated projections close to 120,000 barrels per day at the Liza-1 oil rig located within the Stabroek block. By itself, the news pointed to an inflexion point to hitherto energy-starved Guyana, whose needs are served by the import of 15,000 barrels of oil products per day[4]. The mere prospects of a steady domestic supply of fuel for power generation heralds new times for the country with the highest electricity prices in the region.

From 2015 to 2018, new developments have piled-up and first oil is on its way to becoming a game changer for Guyana. A first highly favourable factor is the rapid maturity of the Liza-1 production site, which is expected to begin delivering oil and gas production as soon as the first quarter of 2020[5].

A second relevant feature of the first find has to do with the high quality of Guyanese oil, which thus can find its way to lucrative markets. But perhaps it is the third factor in the roadmap toward first oil in Guyana that augurs sustained prosperity in the industry: the vast magnitude of recoverable reserves. Since 2015, ExxonMobil has made a total of ten discoveries: the Liza-1, Liza-2 (Liza Deep), Payara, Snoek, Turbot, Ranger, Pacora, Longtail, Hemmerhead and Pluma test wells. Current estimates put potential reserves above 5 billion barrels of oil for the Stabroek block alone, which makes Guyana one of the top five oil powerhouses in the Western Hemisphere and could lead to a production of 750,000 barrels per day[6].

Table 2. The emerging oil and gas sector in Guyana.

The succession of lucrative finds in several areas of the Stabroek block prompted oil companies with concessions in the adjacent Orinduik block to scale-up exploration activities. As a result, in September 2018, it was announced that commercially recoverable oil reserves in the Orinduik block may be close to 2.9 billion barrels of oil[7].

While the concession over the Stabroek block that is expected to deliver first oil in Guyana was allocated to the consortium led by ExxonMobil, many international companies in the energy sector are showing interest in Guyana.

As of 2018, the list of major oil companies that hold rights to develop oil resources of maritime blocks includes Total, Tullow Oil, and EcoAtlantic (Orinduik block); Repsol and Tullow Oil (Kanuku block); Anadarko (Roraima block); Ratio Oil (Kaieteur block); Esso, MidAtlantic and JHI (Canje block); and CGX (Demerara and Corentyne blocks)[8].

Knowledge-sharing between Mexico and Guyana in engineering expertise and environmental enforcement in the oil and gas industry.

International experiences suggest that, for Guyana to be able to secure the maximum benefits from its newly discovered energy resources, the country needs to bridge a significant gap in terms of national institutions, domestic capacities and human capital. On the road towards first oil, is the activation of bilateral and multilateral partnerships in order to foster knowledge-sharing and capacity-building in strategic areas concerning oil and gas.

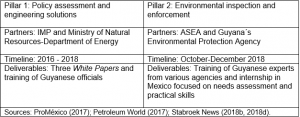

Mexico’s background as a leading producer of oil and gas encompassing more than a century of both inland and offshore oil exploitation makes the country a potential development partner for Guyana[9]. Willing to address the opportunities of demand-driven and results-oriented technical cooperation, the Mexican Agency for International Development Cooperation (AMEXCID) facilitated the institutional dialogue that made it possible for the Mexican Institute for Petroleum (IMP) to become the first international partner to sign a Memorandum of Understanding with the Government of Guyana[10]. In March 2017, the IMP and the Ministry of Natural Resources started the execution of an MOU focused on three white papers: an energy production/energy consumption matrix; a catalogue of international best practices in oil and gas regulation: and a human resources strategy[11].

Since the IMP broke new ground to enter an MOU with Guyana, two other international partners have formalised MOUs with the country: Trinidad and Tobago in September 2018[12], and the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador in October 2018[13].

While the collaboration with the IMP is aimed at fostering engineering capacities, the holistic enhancement of Guyanese institutions requires a parallel pillar of technical cooperation to address environmental enforcement and regulation of the oil and gas industry. In October 2018, the Mexican Agency for Safety, Energy, and the Environment (ASEA) conducted a first training workshop with the participation of more than a dozen agencies of the Guyanese government[14]. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has taken the lead in the bilateral partnership with ASEA in order to jumpstart the in-premises training in ASEA’s headquarters and on oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico for Guyanese officials. This project has attracted financial support from both the Inter-American Development Bank and AMEXCID[15].

Table 3. The two-pronged Mexico-Guyana collaboration in capacity-building for the emerging oil and gas sector.

The Mexican-Guyanese experience in fostering trade facilitation in agriculture.

While the commercial exploitation of oil and gas holds vast promise for Guyana, the first finds in 2015 coincided in time with the announcement from one of the most important clients for Guyanese rice putting an end to bilateral deals that in prior years had allowed Guyana to export close to 37,000 tons of grain. As the national production in 2016 was expected to be nearly 534,000 tons of rice[16], the country faced the need to develop new markets for a cash crop that over the years has proved to be a steady foreign-currency earner and a significant source of jobs.

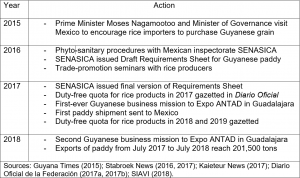

In October 2015, the Government of Guyana approached the Mexican government in order to promote the commercialization of Guyanese grain[17]. Since there were no precedents of the food product having ever been exported to Mexico, the need arose for a comprehensive strategy of economic diplomacy to be put in place by the Mexican authorities in order to address the Guyanese request.

As trade facilitation has long been considered an integral part of the modern practice of international development cooperation, specific actions in the field of economic diplomacy should be put in place following the same criteria as those executed in the field of technical cooperation, namely, the initiatives should be demand-driven, country-appropriate, and results-oriented.

The first major barrier facing exporters of food products vying to enter a new market is the need to clear phyto-sanitary requirements and inspections. Given that no Guyanese grain had ever been exported to Mexico, rice producers had to be educated regarding the legal procedures set by the country´s plant health inspectorate, SENASICA. The initial analysis of Guyanese grain were submitted to SENASICA early in 2016, but the final Requirements Sheet was issued in the first quarter of 2017[18].

A second hurdle that can be even more time-consuming than plant health procedures and usually requires significant expenditure is the task of finding reputable clients who would become pathfinders in the endeavour to bring food products from a novel market and find competitive and practicable solutions in the area of logistics.

Since the international travel costs of business match-making endeavours can be prohibitive for individual producers, the Embassy of Mexico held information workshops in rice-producing regions[19] and teamed-up with the Guyana Rice Development Board in order to organize the first-ever business mission to Mexico, which in March 2017 participated at the largest Supermarket Trade Fair in Latin America, Expo ANTAD in Guadalajara[20]. In order to facilitate translation services and information kits to address the concerns of potential buyers, the Embassy obtained a voluntary liaison from the economics department of the local university.

The economic diplomacy efforts put in place to facilitate the commercialisation of Guyanese grain began delivering results by the end of the second quarter of 2017, and the first shipment of 17,000 tons of paddy was sent to Mexico in July 2017[21].

The activation of grain imports from Guyana included a time-sensitive factor, as the Mexican government set a 150,000 tons duty free quota for rice and paddy that was to be implemented on a first-come, first served basis from March to December 2017[22].

Taking into account that trade in commodities and food products closely tracks competitive prices and opportunities of arbitrage, the introduction of temporary import-tax concessions (which Mexican authorities made available for all rice producing countries on an equal-footing basis) became a relevant element of trade facilitation efforts and ultimately played an important role in securing the inking of contracts between Guyanese producers and Mexican companies.

According to official data from the customs bureau, from July 2017 to July 2018, Guyanese exporters shipped more than 201,500 tons of paddy to Mexico[23], which made Mexico the world´s largest destination for Guyana´s grain.

Trade facilitation mechanisms proved instrumental, especially the decision announced by the Mexican authorities in December 2017 to set new duty-free quotas for the years 2018 and 2019, which amounted to 150,000 tons of rice products for each year[24].

Table 4. The Mexico-Guyana experience in economic diplomacy and technical assistance to facilitate trade in rice products 2015-2018.

Conclusions: A pressing challenge to turn potential into development achievement.

As Guyana’s recent oil discoveries are expected to start bringing vast revenues from the year 2020 onwards, the country could well be on the verge of entering an era of economic expansion and sustained development. Given that the commercial exploitation of Guyanese oilfields will be based on Production-Sharing Agreements with major international oil companies, the country will not need to raise any government debt to finance the huge investment required by offshore projects. Thus, every extra dollar from the energy sector will mean an actual increment to the national income and contribute to effect a change for the benefit of the country and to the welfare of the Guyanese people.

The road ahead for Guyana, however, is not exempt of significant challenges. A potential issue that elicits justified concerns relates to the hitherto untested absorption capacity of the Guyanese economy and the need to put in place expedient solutions to address current and emerging infrastructure bottlenecks while the energy industry expands rapidly. The amount of direct investment already committed by the international oil companies to develop the Liza-1 project, in excess of USD 4.4 billion dollars[25], is vastly greater than Guyana´s Annual GDP of USD 3 billion dollars. Regardless of the corporate capacities of oil multinationals in managing such a big project, the sheer magnitude of the mobilisation of financial, material, and technical resources will have a profound impact on the Guyanese economy as a whole.

The most immediate effect of the massive flow of foreign direct investment will be seen in nominal growth across the economy. The World Bank has pointed to an unprecedented 29% increase in GDP during 2019, as Guyana prepares for the commercial extraction of first oil in 2020[26].

As more test wells move into the production phase, the economic spike can be expected to last for a decade.

Few would expect that, left to act on its own, the invisible hand of markets will prove capable to harness the accelerated economic expansion in order to build a path of sustainable development for Guyana. Indeed, a partnership of free enterprise (both foreign and locally-owned) with the very visible hand of public policy holds the most promise. Thus, a comprehensive strategy aimed at unlocking Guyana’s vast potential requires focused capacity-building efforts in the emerging energy sector and the parallel mobilisation of resources to foster investment and job creation in the sectors that have traditionally been the bulwark of the country’s economy, such as agriculture and forestry.

On the basis of the results delivered by the partnership with Mexico in technical cooperation and economic diplomacy, International Development Cooperation has proved capable of providing useful tools for capacity-building and international trade promotion. As both tasks grow increasingly more complex in the coming years due to an unprecedented rate of economic expansion, development partners should keep in mind that a constant evolution of existing partnerships will be needed in order to make an effective contribution to transformational change in Guyana.

–

* Es Embajador Extraordinario y Plenipotenciario de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos en la República Cooperativa de Guyana, así como Observador Permanente de México ante la Comunidad del Caribe, con sede en Georgetown, Guyana. Es Licenciado en Filología por la Universidad Estatal de Moscú (1991) y cuenta con dos maestrías: una en Filología por la Universidad Estatal de Moscú (1992) y la segunda en Estudios Diplomáticos por el Instituto Matías Romero de México (1994). Es Diplomático de carrera desde 1993 y promovido al rango de embajador desde el año 2009. El Mtro. Iván Sierra ha desempeñado los siguientes cargos:

- Asesor en la Coordinación General de Asesores del Secretario de Relaciones Exteriores (2013-2014).

- Asesor en Asuntos Internacionales en la Presidencia de la República (2008-2012);

- Director General Adjunto de Administración e Información del Instituto de los mexicanos en el Exterior, en la Secretaria de Relaciones Exteriores SRE (2206-2008);

- Dirección de Cooperación Multilateral en la SER (1998-1999); Director de Política de Cooperación, en la SER (1996-1998);

- Subcoordinador de Asesores en el Gobierno de Jalisco (1996);

- Secretario Particular del Director General de Cooperación Técnica y Científica, en la SER (1995-1996).

Ha sido, además, catedrático en el Instituto de Investigaciones Dr. José María Luis Mora, Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México, Centro Interamericano de Estudios de Seguridad Social, Universidad de las Américas- Ciudad de México y en el Centro de Estudios para Extranjeros Universidad de Guadalajara.

–

Referencias:

- CARICOM Secretariat (2005): CARICOM. Our Caribbean Community. An Introduction, Ian Randle Publishers, Kingston.

- Diario Oficial de la Federación (2017a): Acuerdo que modifica al diverso por el que se dan a conocer los cupos para importar carne de res y arroz, Secretaría de Gobernación, Mexico, 26.12.2017.

- Diario Oficial de la Federación (2017b): por el que se dan a conocer los cupos para importar carne de res y arroz, Secretaría de Gobernación, Mexico, 1.3.2017.

- ExxonMobil (2018): “Exxon Guyana Project Overview” available at https://corporate.exxonmobil.com, retrieved 30.10.2018.

- Guyana Chronicle (2017): Guyana commences paddy export to Mexico, Georgetown, 1.7. 2017.

- Guyana Energy Agency (2016): Annual Report 2016, GEA, Georgetown.

- Guyana Times (2018a): EcoAtlantic finds 2.9 barrels of oil and gas offshore Guyana, Georgetown, 12.9.2018.

- Guyana Times (2018b): Minister Trotman meets delegation from IMP, Georgetown, 11.5.2018.

- Guyana Times (2015): Guyana, Mexican Govt mulls commercialisation of Guyana´s paddy, Georgetown, 31.10.2015.

- Houston Chronicle (2017): Exxon, partners greenlight $ 4.4 billion project off Guyana, Houston, 16.6.2017.

- Inter-American Development Bank (2018): Caribbean Region Quarterly Bulletin 2018 and Beyond. IDB, Washington, D. C. June 2018.

- Kaieteur News (2017): Guyana aims to penetrate Mexican rice market at food expo, Georgetown, 28.2.2017.

- Petroleum World (2018): Guyana, Canadian Province of Newfoundland and Labrador sign oil and gas cooperation pact available at www.petroleumworld.com, retrieved 18.10.2018.

- Petroleum World (2017): Guyana gets ready with resources of oil industry signs MOUs with Mexican Institute of Petroleum available at petroleumworld.com, retrieved 20.3.2017.

- Private Sector Commission (2017): A Review of the Real Sector of Guyana´s Economy 2017, Georgetown, PSC.

- ProMéxico (2017): Economic Integration of Mexico and Guyana in Negocios, ProMéxico, Mexico, July-August 2017.

- Sierra Medel, Ivan Roberto (2017): Navigating the Perfect Storm: The Contribution of Knowledge-Sharing to Building Economic Resilience in Caribbean Nations in Citlali Ayala Martinez and Ulrich Muller (eds.) Towards Horizontal Cooperation and Multi-Partner Collaboration. Knowledge-Sharing and Development Cooperation in Latin America and the Caribbean. Nomos, Baden-Baden.

- Sistema de Información Arancelaria Vía Internet Secretaría de Economía (2018): SIAVI available at economia-snci.gob.mx, retrieved 14.9.2018.

- Stabroek News (2018a): ExxonMobil makes 10th oil discovery offshore Guyana-reserves now over five billion barrels, Georgetown, 3.12.2018.

- Stabroek News (2018b): EPA staffer interning with Mexican extractive industries agency, Georgetown, 16.11.2018.

- Stabroek News (2018c): New oil deals not likely before 2020-Bynoe, Georgetown, 9.11.2018.

- Stabroek News (2018d): Mexican regulator helping with oil and gas training, Georgetown, 2.10.2018.

- Stabroek News (2017): Guyana cleared for paddy exports to Mexico, Georgetown, 28.3.2017.

- Stabroek News (2016): Ambassador signals big Mexican market for rice, Georgetown, 13.12.2016.

- The Trinidad Guardian (2018): MOU good for T&T, Guyana – analysts, Port of Spain, 21.9.2018.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2017): “World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision”, available at ESA.UN.org, retrieved 10.9.2017.

- World Bank Group (2018a): Macro Poverty Outlook 2018 available at https://data.worldbank.org, retrieved 15.11.2018.

- World Bank Group (2018b): World Development Indicators available at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator, retrieved 15.11.2018.

–

[1] World Bank Group (2018b).

[2] Sierra Medel (2017).

[3] Inter-American Development Bank (2018).

[4]Guyana Energy Agency (2016).

[5] ExxonMobil (2018).

[6] Stabroek News (2018a).

[7] Guyana Times (2018a).

[8] Stabroek News (2018c):

[9] ProMéxico (2017).

[10] Petroleum World (2017).

[11] Guyana Times (2018b).

[12] The Trinidad Guardian (2018).

[13] Petroleum World (2018).

[14] Stabroek News (2018d).

[15] Stabroek News (2018b).

[16] Private Sector Commission (2017).

[17] Guyana Times (2015).

[18] Stabroek News (2017).

[19] Stabroek News (2016).

[20] Kaieteur News (2017).

[21] Guyana Chronicle (2017).

[22] Diario Oficial de la Federacion (2017b).

[23] SIAVI (2018).

[24] Diario Oficial de la Federacion (2017a).

[25] Houston Chronicle (2017).

[26] World Bank Group (2018a).